How to Read Superficially

When a reader is grappling with a challenging text—such as The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam by Muhammad Iqbal—it’s important for the reader to watch out for possible misinterpretations. I don’t mean that one must avoid all misinterpretations—for that is impossible, given the imperfect nature of language and general human fallibility. Rather, I mean that one must remain open-minded in relation to one’s understanding of the text, allowing it to evolve over time. So long as I keep an open mind, I am willing to re-consider my understanding of what the author means, as well as to replace it with a better and more convincing interpretation whenever necessary. In fact, if I take a book or an author seriously, then I must adopt the proper scientific attitude, prioritizing the truth of the matter over all other considerations.

Truth is the fruit of free inquiry and of such docility towards facts as shall make us always willing to acknowledge that we are wrong, and anxious to discover that we have been so.

Charles Sanders Peirce, Collected Papers 6.450

In the process of reading, I cannot afford to let my ego, or my loyalty to anyone, get in the way of what is undoubtedly the primary goal of that activity, i.e., comprehension. Even though misinterpretations are inevitable, the reader can still aim at minimizing such errors by employing good reading strategies, as well as remain eager to correct them as soon as they are recognized. In this respect, the reader needs to watch out for both Type I and Type II errors. The former refers to “false positive” conclusions, i.e., when the reader finds something in the text that isn’t there, whereas the latter refers to “false negative” conclusions, i.e., when the reader doesn’t find what is, in fact, present in the text. Seeing too much can be just as problematic as seeing too little. Good reading strategies can reduce the chances of both types of misinterpretation.

In reading, just as in any other endeavor, one must begin by clarifying one’s intention. Let’s suppose you want to learn about a topic that is primarily conceptual or theoretical, as opposed to practical, and you have decided that reading a book is going to help you gain the desired understanding. That’s the first step—knowing why you’re doing what you’re about to do. The second step is to choose a book that represents the optimum level of difficulty. Specifically, you want to read a book that is situated within your “learning zone.” That’s because books that belong in your “comfort zone” may provide useful information but they aren’t very helpful for constructing new knowledge. On the other hand, books that are currently in your “panic zone” are, by definition, beyond your current ability to understand; struggling with such books may not be a good use of your time. Once you’ve chosen a book, the third step is to read it superficially. Below I will explain what “superficial reading” means and how it can help reduce the chances of misinterpretation. But first, I’d like to discuss what these three zones are all about.

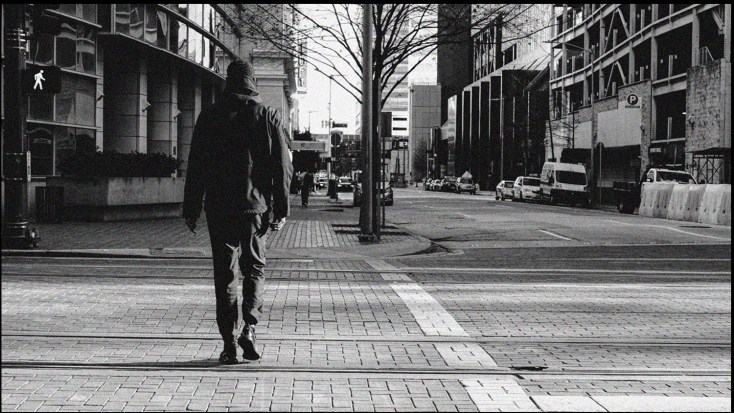

We have all heard that it is necessary to step out of one’s comfort zone in order to experience any growth, but we are rarely given the full picture of exactly what this means. Essentially, comfort zone refers to that psychological state when you are doing something that you have done many, many times before; you know that nothing can go wrong, and so your comfort level is at its maximum. For example, walking on a footpath or a sidewalk is well within most people’s comfort zone.

But suppose you are asked to hop on a tightrope that has been stretched above Niagara Falls, and then walk from one end to the other. The chances that you’ve done this before are pretty slim. In all likelihood, you have zero skill in doing anything even remotely similar to what the man pictured below is doing. In fact, just imagining yourself on the wire, with the roaring and gushing waters below, is probably enough to make you feel nervous. While neither you nor I will ever find ourselves in precisely this situation, I am sure that the basic experience is not alien to anyone. We have all been to the panic zone—we all know what it feels like to be out of our depth, when we have bitten more than we can chew. The panic zone refers to the psychological state in which we are faced with a task that is absolutely impossible for us to accomplish. We can see that everything is about to go horribly wrong, and so our comfort level is at its lowest.

Between the comfort zone and the panic zone is a very interesting and enjoyable place—the learning zone. It refers to that psychological state when you are trying to do something that is somewhat harder than what you can easily do, but it is not completely beyond your ability. In such a state, your comfort level is neither too high nor too low, for the task before you is neither too easy nor too difficult. You are facing a challenge that requires you to call upon all of your skills and resources and to pay very close attention to what you’re doing. You know that mistakes and failures will inevitably happen, but you aren’t bothered by them because your highest priority is learning and not impressing other people. When you are in the learning zone, you feel alert and relaxed at the same time.

If walking on the sidewalk is well within my comfort zone, and walking on a tightrope above Niagara Falls is at the far end of my panic zone, here’s what I might do in my learning zone:

A key feature of the learning zone is that the longer you stay in it, the more it expands. When the learning zone expands, it does so by taking over the adjacent territory of the panic zone. This is another way of saying: “practice makes perfect.” As the learning zone expands, you can expect that what was previously impossible will gradually become possible, and what was previously difficult will become increasingly easy. Expanding the learning zone is really a matter of increasing one’s learning capacity, a topic I have discussed before.

In the context of learning with the help of a book, you want to choose a text that represents the optimum level of difficulty. If it’s too easy, you’d remain stuck in your comfort zone; if it’s too hard, you’d find yourself in the panic zone. It’s only when the level of challenge that a text poses is just right that the reader is going learn the most. This is basically the Goldilocks’ Principle, as applied to the activity of “learning by reading.”

Let’s suppose the book in front of you poses just the right level of difficulty. At this point, your reading strategy becomes decisive. One of most effective strategies for reading a challenging book is to first become familiar with its structure and content before attempting a deeper dive. There are at least two reasons for taking this approach. First, many of us tend to overestimate the difficulty posed by a book while underestimating our own learning capacity. One reads the first couple of pages of a book, realizes that it’s not making perfect sense, and concludes that it is too hard to understand—except that such a judgment is often premature. In most cases, our inability to understand a text right away simply means that we need to read it more than once, not that the text itself is beyond our comprehension.

Here’s a nice description of this phenomenon:

Everyone has had the experience of struggling fruitlessly with a difficult book that was begun with high hopes of enlightenment. It is natural enough to conclude that it was a mistake to try to read it in the first place. But that was not the mistake. Rather it was in expecting too much from the first going over of a difficult book.

Mortimer J. Adler & Charles Van Doren. How to Read a Book (1972), p. 36

Second, struggling with confusing terminology or baffling sentences is not very productive when you are reading a book for the first time. At that early stage, focusing on the smaller units of the text, such as individual words or sentences, can easily lead to misinterpretations; you may see either too much in the text or too little. To avoid this, the reader has to acquire an overall picture of the whole text before analyzing any of its smaller components. That is because the whole sheds light on the parts just as the parts illuminate the whole. This may sound circular, but the process of learning with the help of a challenging book is best imagined as a spiral—our understanding expands every time we move from interpreting the parts to picturing the whole, and vice versa.

Consider a different analogy that makes the same point. The first reading of a difficult book is like meeting a person for the first time. We don’t expect to learn everything about the other person in that first meeting, for then we would probably make hasty assumptions based on a few initial impressions. Instead, it is prudent to reserve any judgments until we have gotten to know the other person very well, and that can only happen by spending a lot of time together. The same is true for reading a book that has a reputation of being both challenging and insightful.

Because of these two reasons, it is important to develop at least some degree of familiarity with the structure and content of the book as a whole, before embarking upon a deep and thorough analysis. To develop that initial familiarity, what we need is the permission to read the entire text without full understanding. That’s because many of us have been socialized into believing that the purpose of reading is comprehension, and therefore it is a waste of time and effort to read anything that we don’t immediately comprehend. The first proposition is true, but the second is a non sequitur that unnecessarily holds us back, discouraging us from venturing outside our comfort zone.

It is perfectly fine to read a book while understanding only bits and pieces, so long as (1) you know that the book is worth reading, and (2) you are willing to read it as many times as necessary. Reading an entire book without fully understanding everything it says is the only way to gain a general sense of the whole, and that is why it is a necessary prerequisite for analytical reading. There happens to be an actual rule that not only gives us the permission to read like this but also requires us to do so.

That rule is simply this: In tackling a difficult book for the first time, read it through without ever stopping to look up or ponder the things you do not understand right away.

Mortimer J. Adler & Charles Van Doren. How to Read a Book (1972), p. 36

This is called “superficial reading.” But please note that the word “superficial” does not refer to reading inattentively, or in a careless and sloppy manner. It means being at peace with less-than-perfect understanding, knowing that each subsequent reading will only improve one’s comprehension.

To read a book superficially is to read the entire text without stopping to investigate anything that one doesn’t immediately understand. For superficial reading, there are only two instructions that the reader needs to follow: First, read all the way through, and second, focus on what makes sense, not on what doesn’t.

Pay attention to what you can understand and do not be stopped by what you cannot immediately grasp. Go right on reading past the point where you have difficulties in understanding, and you will soon come to things you do understand. Concentrate on these.

Mortimer J. Adler & Charles Van Doren. How to Read a Book (1972), p. 36

When we expect too much from our first reading, we end up focusing on those parts of the text that we find difficult or confusing. Focusing on what we don’t understand slows down our progress, doesn’t improve comprehension, increases the chances of misinterpretation, distracts us from grasping the bigger picture, and may even discourage us to the point of giving up. The second reading is always more productive, but you can’t read a book the second time around if you allow the difficulties of the text to prevent you from finishing your first reading. Focusing on what you do understand is therefore a much more effective approach when you are reading a challenging text for the first time.

Superficial reading is not sufficient on its own, but it is necessary. It is what prepares the reader for a deeper engagement with the text during subsequent readings. Analytical reading is a lot more productive when the reader is familiar with the structure and content of the text, and superficial reading is precisely the strategy for gaining that familiarity.